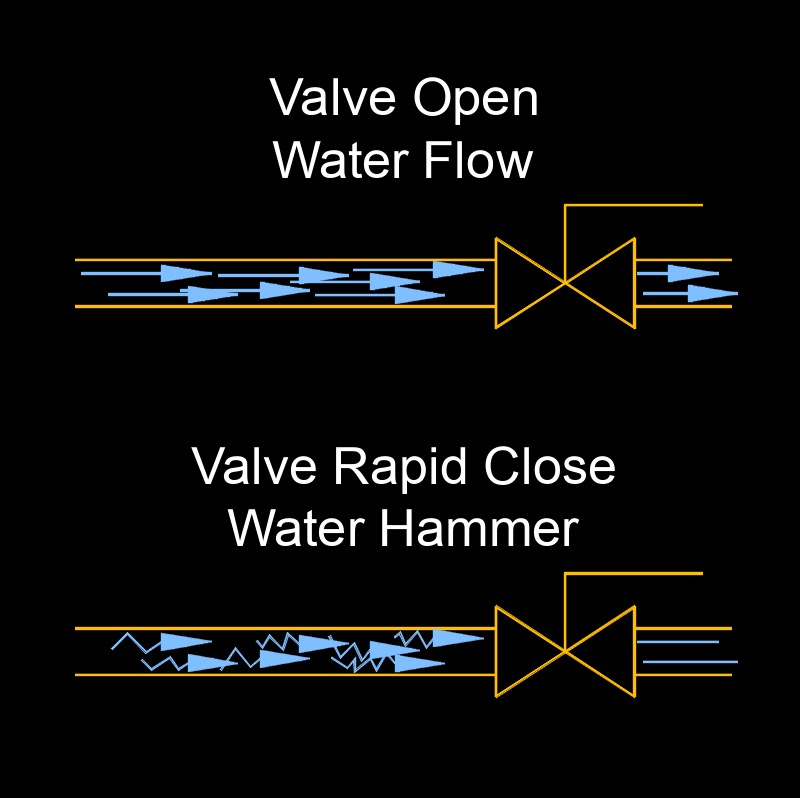

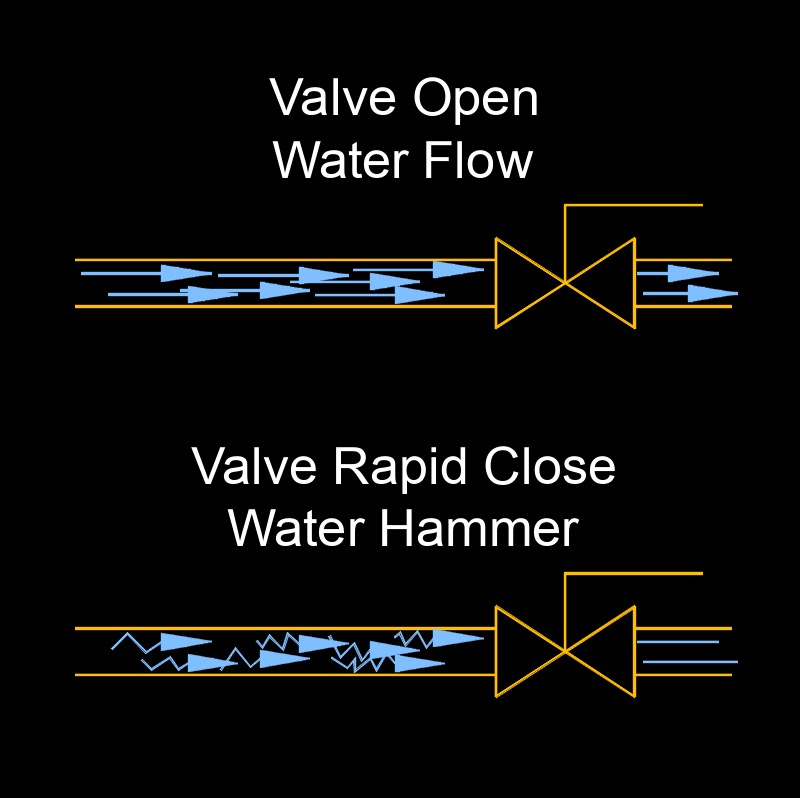

Water hammer, abbreviated as \(WH\), also called hydraulic shock, surge pressure or fluid hammer, is a pressure surge or shock wave that occurs in a fluid-filled pipe system when the flow of a liquid, most commonly water, is suddenly stopped or rapidly changed in velocity. This typically happens when a valve closes quickly, a pump suddenly stops, or a downstream blockage occurs. Because liquids are only slightly compressible and pipes are elastic to a limited extent, the sudden deceleration of the moving fluid causes a rapid rise in pressure that propagates through the pipe as a high-speed pressure wave. This transient pressure increase can greatly exceed the normal operating pressure of the system and may produce loud banging noises, vibration, pipe movement, joint failure, or even pipe rupture. The magnitude of the pressure surge depends on factors such as the fluid velocity, fluid density, speed of sound in the fluid-pipe system, pipe material, pipe length, and the rate at which the valve or pump action occurs. Water hammer is analyzed in fluid dynamics using transient flow theory, and its effects can be mitigated through devices such as air chambers, surge tanks, pressure relief valves, slow-closing valves, and proper system design.

Water hammer, abbreviated as \(WH\), also called hydraulic shock, surge pressure or fluid hammer, is a pressure surge or shock wave that occurs in a fluid-filled pipe system when the flow of a liquid, most commonly water, is suddenly stopped or rapidly changed in velocity. This typically happens when a valve closes quickly, a pump suddenly stops, or a downstream blockage occurs. Because liquids are only slightly compressible and pipes are elastic to a limited extent, the sudden deceleration of the moving fluid causes a rapid rise in pressure that propagates through the pipe as a high-speed pressure wave. This transient pressure increase can greatly exceed the normal operating pressure of the system and may produce loud banging noises, vibration, pipe movement, joint failure, or even pipe rupture. The magnitude of the pressure surge depends on factors such as the fluid velocity, fluid density, speed of sound in the fluid-pipe system, pipe material, pipe length, and the rate at which the valve or pump action occurs. Water hammer is analyzed in fluid dynamics using transient flow theory, and its effects can be mitigated through devices such as air chambers, surge tanks, pressure relief valves, slow-closing valves, and proper system design.

Water Hammer Happens When

Steady-State Flow Exists - Liquid (commonly water) flows through a closed pipe at a certain velocity under normal operating pressure. The fluid has momentum due to its mass and velocity.

Sudden Change in Flow Condition - A rapid event occurs, such as a valve closing quickly, a pump stopping abruptly, or a check valve slamming shut. The fluid downstream of the closure stops almost immediately.

Fluid Inertia Causes Compression - The upstream fluid, still moving due to

inertia, cannot stop instantaneously. Because liquids are only slightly compressible and pipes are slightly elastic, the fluid near the closure point compresses and the pipe wall expands slightly.

Formation of a High-Pressure Wave - This compression generates a sharp rise in pressure at the point of flow stoppage. A pressure wave (shock wave) forms and begins traveling upstream through the pipe at the acoustic wave speed of the fluid–pipe system.

Wave Propagation Through the Pipe - The pressure wave moves rapidly along the pipe, temporarily increasing pressure as it passes each point. The speed of this wave depends on the fluid properties (

density and

bulk modulus) and pipe characteristics (material and wall thickness).

Reflection of the Pressure Wave - When the wave reaches a boundary (such as a reservoir, pump, or pipe end), it reflects. Depending on the boundary condition, the reflected wave may be a high-pressure wave or a low-pressure (rarefaction) wave.

Pressure Oscillation - The reflected waves travel back and forth within the pipe, creating oscillating pressure fluctuations. These oscillations gradually diminish due to frictional losses and damping in the system.

Return to Equilibrium - Over time, the transient pressure surges dissipate, and the system stabilizes at a new steady-state pressure condition.

Water Hammer can have Various Negative Effects

Pipe Damage or Rupture - The sudden pressure surge can greatly exceed the pipe’s design pressure, leading to cracking, bursting, or complete pipe failure—especially in older, brittle, or improperly supported systems.

Joint and Fitting Failure - Couplings, flanges, threaded joints, and gaskets may loosen, leak, or fail due to repeated high-pressure spikes and mechanical shock.

Valve and Pump Damage - Rapid pressure fluctuations can damage valve seats, discs, and stems. Pumps may experience mechanical stress, seal failure, bearing damage, or reverse rotation in severe cases.

Cavitation and Column Separation - If the

pressure drops below the liquid’s vapor pressure during the transient cycle, vapor cavities can form. When these cavities collapse, they can cause localized shock damage and material erosion.

Excessive Noise - Water hammer often produces loud banging or knocking sounds as the pressure wave interacts with pipe walls and supports.

Pipe Movement and Vibration - The

force associated with the pressure surge can cause pipes to shift, vibrate, or strike supports and structural elements, leading to fatigue damage over time.

Structural Damage to Supports - Repeated dynamic loads can weaken pipe supports, anchors, brackets, and surrounding structural components.

System Downtime and Maintenance Costs - Damage caused by water hammer can result in leaks, emergency repairs, operational interruptions, and increased maintenance expenses.

Reduced Equipment Lifespan - Continuous exposure to transient pressure shocks accelerates wear and fatigue in system components.

What can be done to Mitigate Water Hammer

Air Chambers (Air Cushions) - Installing vertical air chambers near quick-closing valves provides a compressible air pocket that absorbs pressure spikes. The air compresses when a surge occurs, reducing peak pressure.

Water Hammer Arrestors - These are sealed devices containing a piston or diaphragm with compressed gas behind it. When a pressure surge occurs, the device absorbs the shock energy and dampens the pressure wave.

Surge Tanks or Standpipes - In larger systems, surge tanks allow fluid to move into or out of the tank during transient events, limiting pressure extremes. They are commonly used in pumping stations and long pipelines.

Pressure Relief Valves - Relief valves open automatically when pressure exceeds a set limit, releasing fluid to prevent excessive overpressure.

Pump Control Strategies - Soft-start and soft-stop pump controls reduce rapid acceleration or deceleration of flow. Variable frequency drives (VFDs) allow controlled changes in pump speed, minimizing transients.

Proper Pipe Support and Anchoring - Adequate

supports, guides, and anchors help resist dynamic forces and prevent pipe movement during transient events.

Pipe Material and Thickness Selection - Selecting pipe materials and wall thicknesses capable of withstanding transient pressures reduces the risk of rupture.

System Layout Optimization - Avoiding long straight runs without protection, minimizing sudden directional changes, and designing for appropriate flow velocities reduce water hammer risk.

Maintaining Appropriate Flow Velocities - Lower operating velocities reduce the potential surge magnitude because water hammer pressure is proportional to fluid velocity change.

Water hammer, abbreviated as \(WH\), also called hydraulic shock, surge pressure or fluid hammer, is a pressure surge or shock wave that occurs in a fluid-filled pipe system when the flow of a liquid, most commonly water, is suddenly stopped or rapidly changed in velocity. This typically happens when a valve closes quickly, a pump suddenly stops, or a downstream blockage occurs. Because liquids are only slightly compressible and pipes are elastic to a limited extent, the sudden deceleration of the moving fluid causes a rapid rise in pressure that propagates through the pipe as a high-speed pressure wave. This transient pressure increase can greatly exceed the normal operating pressure of the system and may produce loud banging noises, vibration, pipe movement, joint failure, or even pipe rupture. The magnitude of the pressure surge depends on factors such as the fluid velocity, fluid density, speed of sound in the fluid-pipe system, pipe material, pipe length, and the rate at which the valve or pump action occurs. Water hammer is analyzed in fluid dynamics using transient flow theory, and its effects can be mitigated through devices such as air chambers, surge tanks, pressure relief valves, slow-closing valves, and proper system design.

Water hammer, abbreviated as \(WH\), also called hydraulic shock, surge pressure or fluid hammer, is a pressure surge or shock wave that occurs in a fluid-filled pipe system when the flow of a liquid, most commonly water, is suddenly stopped or rapidly changed in velocity. This typically happens when a valve closes quickly, a pump suddenly stops, or a downstream blockage occurs. Because liquids are only slightly compressible and pipes are elastic to a limited extent, the sudden deceleration of the moving fluid causes a rapid rise in pressure that propagates through the pipe as a high-speed pressure wave. This transient pressure increase can greatly exceed the normal operating pressure of the system and may produce loud banging noises, vibration, pipe movement, joint failure, or even pipe rupture. The magnitude of the pressure surge depends on factors such as the fluid velocity, fluid density, speed of sound in the fluid-pipe system, pipe material, pipe length, and the rate at which the valve or pump action occurs. Water hammer is analyzed in fluid dynamics using transient flow theory, and its effects can be mitigated through devices such as air chambers, surge tanks, pressure relief valves, slow-closing valves, and proper system design.