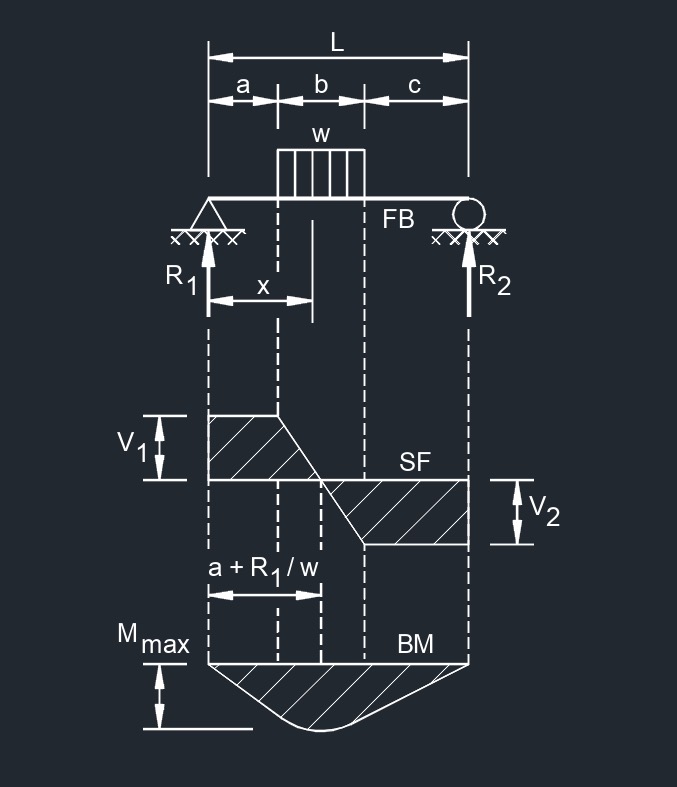

Beam Loading

Beam loading simply means the forces and effects applied to that beam and how the beam reacts to stay stable and carry those forces safely. Loads come from all sorts of sources: the beam's own weight (called self-weight or dead load), the weight of people walking across a floor, vehicles on a bridge, heavy equipment or machinery, snow piling up on a roof, wind pushing sideways, or even earthquakes shaking things around. When any of these loads act on the beam, it creates internal resistances, mainly bending moments (which try to curve or sag the beam) and shear forces (which try to slide one part of the beam past another) to counteract the applied forces and keep everything from collapsing.

Beam loading simply means the forces and effects applied to that beam and how the beam reacts to stay stable and carry those forces safely. Loads come from all sorts of sources: the beam's own weight (called self-weight or dead load), the weight of people walking across a floor, vehicles on a bridge, heavy equipment or machinery, snow piling up on a roof, wind pushing sideways, or even earthquakes shaking things around. When any of these loads act on the beam, it creates internal resistances, mainly bending moments (which try to curve or sag the beam) and shear forces (which try to slide one part of the beam past another) to counteract the applied forces and keep everything from collapsing.

A beam is a long, straight structural member, usually horizontal, that's built to handle loads mostly through bending. Think of everyday examples like the floor joists under your house, the big girders supporting a bridge deck, the boom on a crane, or even a simple wooden shelf holding books. These members are designed so that when weight or other forces push down (or sometimes pull or twist) on them from the side, they resist mainly by flexing and bending rather than compressing or stretching end-to-end like a column does.

Loads show up in different patterns, and each pattern changes how the beam behaves. A point load is like a single heavy force hitting one specific spot, for instance, a big machine sitting right in the middle of a platform or a column resting on the beam below. A distributed load spreads out more evenly along the length, such as the uniform weight of a concrete floor slab, roofing materials, or a blanket of snow. Engineers also deal with moments (twisting or rotational forces applied at a point, like from a cantilevered sign or certain connections) and dynamic loads (forces that aren't steady, such as vibrations from machinery, moving traffic, or sudden impacts). The exact type, size, and position of these loads make a huge difference: they determine how much the beam bends or sags, where the highest stresses build up (often causing tension on one side and compression on the other), and whether the beam can handle everything without problems.

Analyzing beam loading is one of the most important steps in structural design. Engineers calculate things like bending stress (how much the material is stretched or squashed from curving), shear stress (from sliding forces), and deflection (how far the beam sags or moves under load). The goal is to make sure the beam is strong enough not to break, stiff enough so it doesn't sag too much (which could crack finishes, make floors feel bouncy, or damage connected elements), and safe overall under the worst expected conditions. Doing this properly prevents real-world failures like cracking, excessive drooping, or in extreme cases, complete collapse.