Poisson's Ratio

Poisson's Ratio Formula |

||

|

\( \mu \;=\; \dfrac{ \varepsilon_t }{ \varepsilon_l }\) (Poisson's Ratio) \( \varepsilon_t \;=\; \mu \cdot \varepsilon_l \) \( \varepsilon_l \;=\; \dfrac{ \varepsilon_t }{ \mu }\) |

||

| Symbol | English | Metric |

| \( \mu \) (Greek symbol mu) = Poisson's Ratio | \( dimensionless \) | \( dimensionless \) |

| \( \epsilon_t \) (Greek symbol epsilon) = Transverse Strain (Direction of Load) | \(in\;/\;in\) | \(mm\;/\;mm\) |

| \( \epsilon_l \) (Greek symbol epsilon) = Longitudinal Strain (Right Angle to Load) | \(in\;/\;in\) | \(mm\;/\;mm\) |

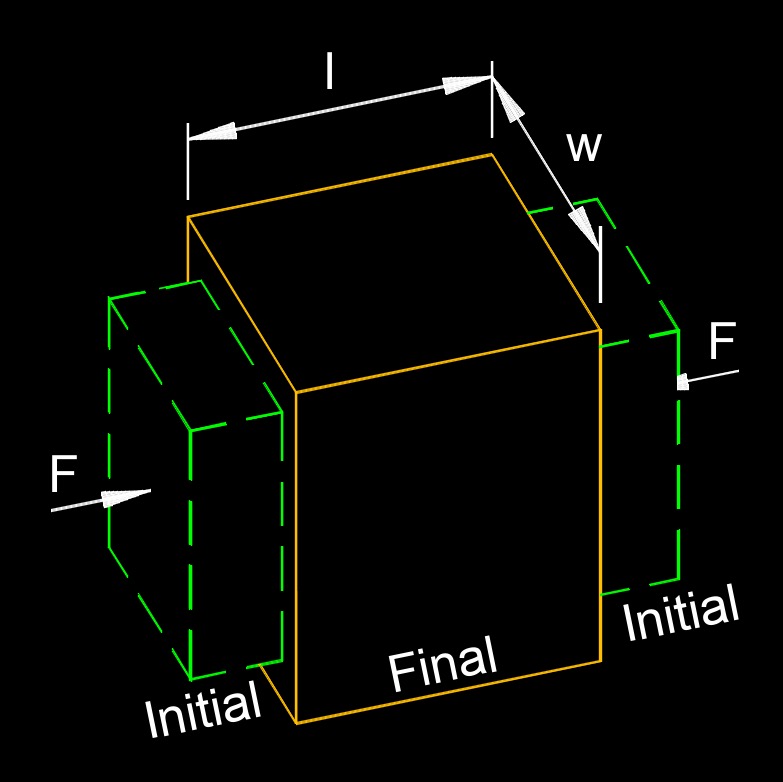

Poisson’s ratio, abbreviated as \(Po\), \(\mu\) or \(\nu\), isn’t a dimensionless number in the same sense as those in fluid dynamics, it’s a material property, a dimensionless ratio that describes how a material deforms under stress. Specifically, it measures the ratio of transverse strain (sideways contraction or expansion) to axial strain (lengthwise stretch or compression) when a material is stretched or compressed elastically. It’s a key concept in solid mechanics, showing up in engineering, materials science, and structural design.

Poisson’s ratio, abbreviated as \(Po\), \(\mu\) or \(\nu\), isn’t a dimensionless number in the same sense as those in fluid dynamics, it’s a material property, a dimensionless ratio that describes how a material deforms under stress. Specifically, it measures the ratio of transverse strain (sideways contraction or expansion) to axial strain (lengthwise stretch or compression) when a material is stretched or compressed elastically. It’s a key concept in solid mechanics, showing up in engineering, materials science, and structural design.

Poisson's ratio is a measure of the degree of deformation that a material undergoes when subjected to an external stress. It is always negative or between 0 and 0.5 for most materials, indicating that when a material is compressed or stretched, it will contract or expand laterally. The value of Poisson's ratio depends on the type of material and its structure, and it is an important parameter in engineering and materials science, especially in the design of structures that require elasticity and resilience, such as buildings, bridges, and aircraft.

- See Article - Poisson's Ratio of an Element

Poisson's Ratio Interpretation

-

Positive Poisson’s Ratio (0 < \(\mu\) < 0.5) - Most common materials—like metals, rubber, or concrete, contract sideways when stretched (or expand sideways when compressed). A higher \(\mu\) means more lateral deformation relative to axial strain.

-

\(\mu\) ≈ 0 - Minimal lateral deformation, good for applications where you want dimensional stability sideways.

-

\(\mu\) ≈ 0.5 - The material is nearly incompressible (volume stays constant), like rubber or soft tissues. Stretch it, and it thins a lot to preserve volume.

-

-

\(\mu\) = 0.5 - The theoretical maximum for isotropic, incompressible materials. No volume change occurs during deformation, stretch it lengthwise, and it shrinks sideways exactly enough to keep the same volume. This is an idealization approached by rubbery materials.

-

Negative Poisson’s Ratio (\(\mu\) < 0) - Rare, auxetic materials expand sideways when stretched (or contract sideways when compressed). Think of certain foams or engineered structures, pull them, and they get wider. Useful for things like shock absorption or medical implants.

-

\(\mu\) > 0.5 or \(\mu\) < −1 - Theoretically possible in anisotropic materials (crystals), but rare and not physically realistic for most isotropic solids due to stability constraints.

Poisson's Ratio Applications

Engineering - Used to predict how materials behave under load (in structural design or manufacturing).

Geology - Helps understand rock deformation under tectonic stress.

Biology - Relevant for tissues like tendons or cartilage, which exhibit complex elastic properties.

Different materials have different Poisson's ratios. For most common materials, Poisson's ratio falls in the range of 0 to 0.5. Metals generally have Poisson's ratios around 0.3, while rubber-like materials can have Poisson's ratios close to 0.5.